I know exactly where I was when I first read The Sandman. Wood Green Central Library, London, summer of 1999. I was waiting for the librarian to retrieve a book I had ordered, Perfume by Patrick Suskind. She took her time, so I wandered the stacks and came across a copy of The Wake. I flipped it open, turned some more pages, and sat down to finish it in one sitting. I ignored Perfume and borrowed seven more volumes of The Sandman. The alchemy of rich characters, the stories infused with history and the grand mythology of humankind respun in novel ways seized my imagination and would not let go. If you’re reading this, you know exactly what I mean.

I was out of sorts at that time. Carlos Santana was on heavy rotation, I was a year out of medical school, and I’d just returned to London after a gruelling stint as a medical officer in Samoa. I had no idea what specialty to pursue, but after bumming around different departments, I found psychiatry had the least potential for boredom. I started the series of exams, teaching, and hands-on experience required. It’s been ten years since I became a member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and in that time I’ve often reread The Sandman. Whenever I get through The Kindly Ones, I end up thinking, Morpheus dies. Huh. Gaiman’s a dick.

But the writing, the narrative choices, the art, all collude to make Morpheus’ death inevitable. I dealt (and deal) with suicide and the risk of suicide every day at work. I wondered how The Sandman would hold up if subjected to the kind of scrutiny that real world suicides have to undergo.

I set rules for this: I would only consider what happened within the fictional world. Reviews, think pieces, author interviews, or annotations did not concern me. Barthesian death aside, I wanted to interrogate the text forensically to explain why the work grabbed me by the feels.

You know how they say you need motive, means, and opportunity to prove a murder? Well, to show a death was not an accident or prove a person was not “suicide,” three things are needed: a death, at the hand of the victim, with intent to die—the last of which is never as easy as it sounds. Even the presence of a suicide note, for example, doesn’t mean a person intended to die.

[Warning: Detailed spoilers for The Sandman from this point on…]

Here’s what happens in The Sandman: Loki of Asgaard and Puck of Faerie kidnap Morpheus’ chosen successor, Daniel Hall. Lyta Hall, Daniel’s mother, thinks he’s dead, blames Morpheus because of their shared history, and vows revenge.

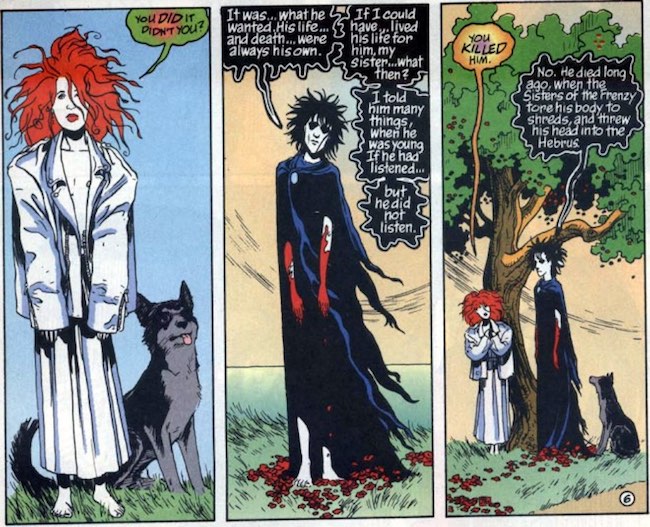

She suffers a psychotic breakdown. While in the throes of psychosis she seeks help from The Kindly Ones (who are also the Furies, the Three Witches, the Fates, etc). Lyta used to be a superhero known as The Fury, an avatar of the Furies (much like her husband Hector Hall was an avatar of Morpheus). The Kindly Ones are commissioned to avenge the spilling of family blood. For complicated reasons, Morpheus had killed his son Orpheus, making him vulnerable to them.

Morpheus recovers Daniel, and has the child brought to the heart of the Dreaming, the place where you and I go to dream. The Kindly Ones begin to destroy the Dreaming, killing the dreams, working their way to the centre. Reluctantly, Morpheus decides to kill Lyta in the waking world. He finds her surrounded by a protective spell cast by his ex-lover, Thessaly. He can break the spell, but his inherent rigidity means he must obey the rules.

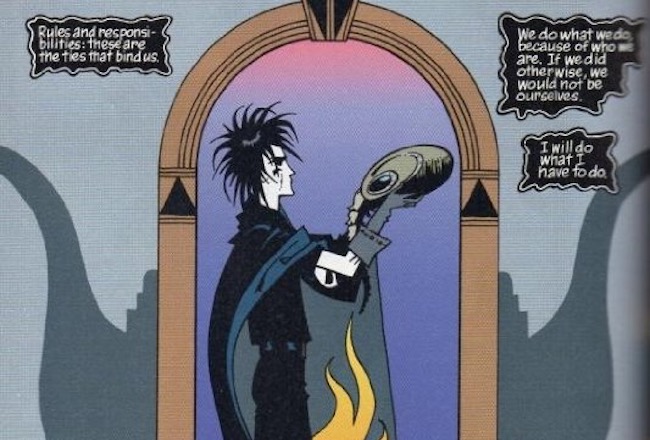

Morpheus returns to the Dreaming, planning to wait the Kindly Ones out, because they can’t harm him there, but he has to fulfil a promise he made to Nuala of Faerie. In so doing, Morpheus renders himself defenceless. By the time he returns the Kindly Ones are in the heart of the Dreaming. Morpheus summons his sister Death, who kills him.

Morpheus dies. It’s not a comic book death (except, technically it is, but you know what I mean). It’s not Elektra getting shivved by Bullseye and using Ninja-voodoo to return, or Superman breaking the industry in the 90s, or Jean Grey rocking that Phoenix regeneration beyond my ability to care. No, Morpheus really dies, with an invisible body, a wake, a funeral.

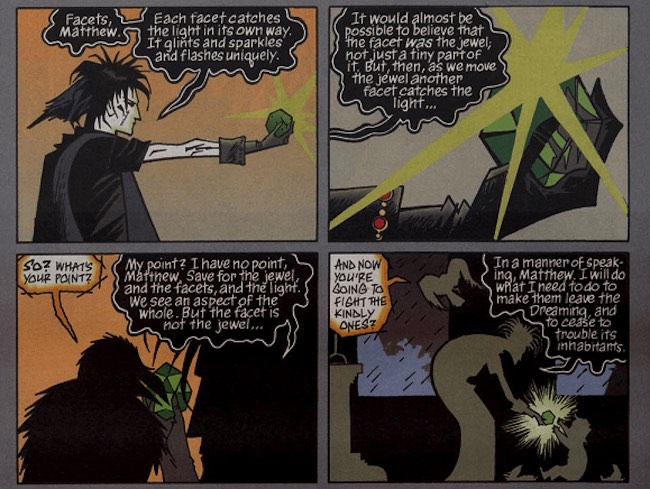

We know from Death’s speech in TKO Chapter 13 that Morpheus orchestrates his own demise:

Death: “The only reason you’ve got yourself into this mess is because this is where you wanted to be.”

Morpheus: “I have made all the preparations necessary.”

Death: “Hmph. You’ve been making them for ages. You just didn’t let yourself know that was what you were doing.”

Buy the Book

The Murders of Molly Southbourne

Morpheus had options. He could have refused to kill Orpheus in the first place, since he did not want to and knew this would make him powerless against the Kindly Ones. He could have killed Lyta Hall. He could have done a lot more to protect Daniel Hall, in order to avoid activating Lyta as a vengeance agent in the first place. He could have refused to fulfil his promise to Nuala. He could have gone with Delirium to her realm, or stayed in Faerie. My favourite fantasy scenario is Morpheus simply refusing to die, a precedent set in the Sandman universe by his friend Hob Gadling; after all, Death is his sister and fond of him, and known to break the rules. Morpheus takes none of these opportunities, and instead chooses to die.

In TKO Chapter 12 he removes the vestments of his office and hands them to his familiar. He throws away his cloak and gauntlet, then he smiles, as if the decision has been made. Loved ones of people who have committed suicide describe an improvement of their mood just prior to the event. Victims also prepare by closing bank accounts, amending wills, and writing letters. Looking at the narrative, is it possible to examine Gaiman’s layering to find out why Morpheus would commit suicide? There are factors to do with his background, his personality, and the fact that he seems to have been depressed at the time of death.

His parents are Time and Night (from Sandman: Overture). Separated a long time ago, neither seems like particularly interested parents.

Night: “Tell me of your siblings. The only one I ever see is Destiny. He comes and he talks. And the little one…”

Morpheus: “Delirium.”

Night: “I see her wandering around here sometimes. She’s changed, though. I don’t know what she wants from me.”

Morpheus: “The same things she always wanted. Your ATTENTION. Your INTEREST. Your LOVE.”

Night appears mercurial, mood changing almost arbitrarily, doling out punishment to Morpheus when he doesn’t do what she wants. Time wishes his children would all leave him alone. Absent, indifferent parents would increase Morpheus’ vulnerability to mental illness.

Check out his siblings, the Endless. In birth order they are Destiny, Death, Dream, Destruction, Desire/Despair (twins) and Delirium. Destiny, the eldest, is blind, walks through a labyrinth reading the book chained to his right wrist. He doesn’t care about anything else, and has no relationships outside family. Death was at first frightening, (as seen in Sandman: Endless Nights) but changed at some point into a bright, cheerful and philosophical Goth. Destruction was jocular and well-liked by his siblings, but turned his back on the family and his office. He indulged in art, cooking, a touch of archaeology, and bad poetry, but never returned to his family.

Desire is gender-fluid, with no consistent pronoun used. They are described as “untrustworthy, acerbic, dangerous and cruel.” They appear to love their twin sister, but otherwise are amoral. They and Morpheus have hated each other for centuries, if not longer. Despair walks around bare-ass naked, has rats for pets, and regularly mutilates herself. Delirium is the youngest and is psychotic with disordered thoughts and impaired reality testing.

Morpheus is closest to Death and Delirium. His most consistent personality trait is inflexibility; however, he can be cruel, vengeful, and petty. He is aloof, focused on his responsibilities and not given to frivolousness. He stands on ceremony and has his own streak of narcissism (an independent risk factor for depression). He forms brief, intense relationships, often with mortals, and sulks or becomes vindictive when the relationships end. He often shows Obsessive-Compulsive personality traits (not OCD; there’s a difference), and as such lacks flexibility, is preoccupied with rules, and is overly sensitive to criticism of his duties.

Personality and background, however, are not enough. Trigger events often create an overlay of depression, which, for Morpheus, was the death of his son Orpheus, and the break-up with Thessaly. Morpheus himself states in TKO Chapter 11 that he killed his son twice.

Morpheus: “And I killed my son. I killed him twice. Once, long ago, when I would not help him; and once…more recently…when I did…”

After breaking up with Thessaly, who did not love Morpheus, he became dejected. The Dreaming was dark and gloomy, with constant rainstorms. Morpheus stops communicating with people and essentially suffers in silence. While he sulks, Delirium turns up with the bright idea that they seek out Destruction. Aside from being a gigantic metaphor-made-flesh, seeking Destruction has deleterious effects—it leads directly to Morpheus killing his son, which triggers depression.

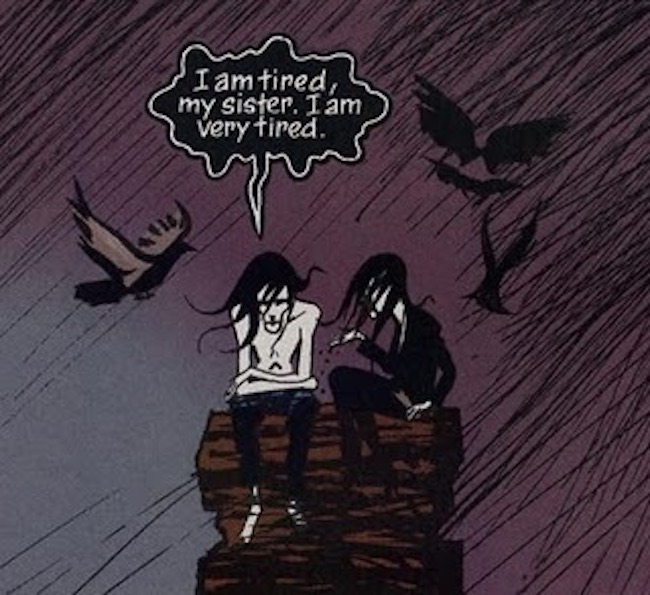

“Since I killed my son…the Dreaming has not been the same…or perhaps I was no longer the same. I still had my obligations…But even the freedom of the Dreaming can be a cage of a kind, my sister.” (TKO Chapter 13)

The extent of his sadness and anhedonia (lack of pleasure) is shown in the excellent art, particularly in TKO Chapter 7 where Morpheus says: “Am I really that disappointing?”

It is interesting that Morpheus gives this as the reason for destroying one of his more frightening nightmares, the Corinthian. “He was a disappointment. I uncreated him.” (TKO Chapter 5). It is as if he believes that being a disappointment is grounds for annihilation, even self-annihilation. Remember what I said about his personality above? Well, that’s why: with his perfectionism and adherence to rules, this would hit him like a gut shot.

Did trauma contribute to the later depression? In Volume 1: Preludes and Nocturnes, Morpheus was captured, robbed, stripped naked and held prisoner by Roderick Burgess. Perhaps a lingering post-traumatic element increased his vulnerability? I’m not convinced of this: he didn’t seem to show any symptoms of PTSD, or even acute trauma. Being naked would not mean much to Morpheus, and the time period is insignificant to him. If anything, this episode was embarrassing to him, and other puissant beings took digs at Morpheus because of it. It’s more likely that he would perceive it as a mark of incompetence in himself, rather than a traumatic event. That said, the trapping happened when he was on the way back from a god-awful battle which saved reality as we know it, but exhausted him beyond imagination. Who knows what damage lingered? Who knows the effect of such a fight on Morpheus? Perhaps he was doomed from the start of the series.

Felo de se or not, any close reading of the work yields layers of rich characterisation detailed enough to tolerate this kind of enquiry, which is to the writer’s credit. It’s difficult to tell if Gaiman planned it all out, but that doesn’t matter. What matters is The Sandman is a complex narrative with masterful characterisation, containing all the breadcrumbs that lead to the moment of suicide. If you change the names of the Endless and remove all the fantastical elements, The Sandman would read as a convincing suicide case report.

If you’ve never read this series you should because it’s damn good fiction. I still read Perfume later in 1999, but mostly I’m grateful to Suskind for leading me to this kick-ass graphic novel series.

Tade Thompson is a consultant psychiatrist and writer. He is the author of the Rosewater trilogy (winner of the Nommo Award and John W. Campbell finalist), The Murders of Molly Southbourne (nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, the British Science Fiction Award, and the Nommo Award), and Making Wolf (winner of the Golden Tentacle Award). Tade’s novella The Survival of Molly Southbourne is forthcoming from Tor.com Publishing. He lives and works in England.

Tade Thompson is a consultant psychiatrist and writer. He is the author of the Rosewater trilogy (winner of the Nommo Award and John W. Campbell finalist), The Murders of Molly Southbourne (nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, the British Science Fiction Award, and the Nommo Award), and Making Wolf (winner of the Golden Tentacle Award). Tade’s novella The Survival of Molly Southbourne is forthcoming from Tor.com Publishing. He lives and works in England.